Eye candy for your travel content

… or rather, a cake in the shape of the vintage suitcase with a camera and a passport

Hat tip to lace & leather

Sensation and Perception: 12 examples of how physical experiences influence attitude and judgment

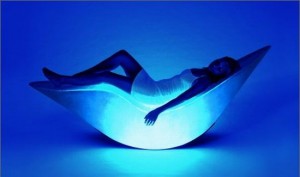

Award winning AlphaSphere "Perception-Furniture" by European Artist sha. It is said that complete relaxation is attained when all the five sense organs (eyes, ears, nose, skin and tongue) of the body are relaxed and remain in perfect harmony with each other.

The more you learn about the brain, the more you realize how wonderfully delusional our brains are. As Anais Nin put it, “We don’t see things as they are. We see things as we are.” Whatever seems real to us may turn out to be a fabrication of our subconscious mind and the senses. How we feel and think about the world influences how we actually see it. Our social perceptions can be shaped by our physical experiences and the attributes of our environment. Here are some intriguing examples from several studies on perception and influence:

- Weight is metaphorically associated with seriousness and importance. Can the weight of an item influence our perception of its importance in real life? Apparently, yes. In one study, job candidates whose resumes were seen on a heavy clipboard were judged as better qualified and more serious about the position.

- In an experiment testing the effects of texture, participants had to arrange rough or smooth puzzle pieces before hearing a story about a social interaction. Those who worked with the rough puzzle were more likely to describe the interaction in the story as uncoordinated and harsh.

- In a test of hardness, subjects handled either a soft blanket or a hard wooden block before being told an ambiguous story about a workplace interaction between a supervisor and an employee. Those who touched the block judged the employee as more rigid and strict.

- In a similar experiment, subjects seated in hard or soft chairs engaged in mock haggling over the price of a new car. Subjects in hard chairs were less flexible, showing less movement between successive offers. They also judged their adversary in the negotiations as more stable and less emotional.

- The difficulty of the task can distort our perception of distance. Researchers have found that hills appear steeper and distances longer when people are fatigued or carrying heavy loads.

- Just holding your body in a certain position can help you remember things faster and more accurately. The subjects were able to remember certain events in their lives faster when they assumed the same positions that their bodies were in when those memories occurred.

- The objects that we want or like appear closer to us than they actually are. For example, participants who had just eaten pretzels perceived a water bottle as significantly closer to them relative to participants who had just drank as much water as they wanted. A $100 bill that participants had the possibility of winning appeared closer than a $100 bill that belonged to the experimenter.

- People in fresh-scented rooms are more likely to engage in charitable behavior. One experiment assessed the subjects’ interest in volunteering for a Habitat for Humanity service project. On a 7-point scale, those amid the fresh scent ranked at a 4.21 interest level, on average, while those in the normal room came in at 3.29. When asked to donate money, 22 percent of the participants in the fresh-smelling room agreed, compared to only 6 percent in the normal room. Follow-up questions found the participants didn’t notice the scent in the room.

- Studies show a link between physical warmth and generosity. Individuals who held a warm beverage viewed a stranger as having warmer personality traits than when holding an iced coffee. In addition to viewing others as more trustworthy and caring, individuals who held a warm object also were more generous with others. It turns out that the insula region of the brain is involved in processing information from both physical temperature and interpersonal warmth, or trust.

- In contrast, social isolation can actually make people feel cold. Researchers asked some subjects to remember a time when they felt socially excluded, such as being rejected from a club, while others recalled memories of being accepted into a group. Afterward, the researchers asked all the participants to estimate the temperature of the room, telling them this task was unrelated to the previous activity and that the building’s maintenance staff simply wanted to know. In general, emotionally chilly memories literally made the subjects feel chillier, even though the room’s temperature remained constant during the experiment. In another study, participants who were made to feel excluded from a game were much more likely to rate higher the appeal of warm food items, such as soup and coffee, than those who had felt socially accepted. They wanted foods that could warm them up.

- People who feel physically clean appear less judgmental. If the jury members washed their hands prior to delivering their verdict, would they judge the crime less harshly? In a series of experiments, students who had washed their hands or read about cleanliness rated certain transgressions to be less wrong compared to the control group. Research also shows the link between disgust and moral judgments.

- People are much more attuned to negative words and can perceive the emotional value of subliminal messages. A subliminal message is a signal or message embedded in another medium, designed to pass below the normal limits of the human mind’s perception. These messages are unrecognizable by the conscious mind, but in certain situations can affect the subconscious mind and can negatively or positively influence subsequent thoughts, behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs. In one study, fifty participants were shown a series of words on a computer screen. Each word appeared on-screen for only a fraction of second – at times only a fiftieth of a second, much too fast for the participants to consciously read the word. The words were either positive (e.g. cheerful, flower and peace), negative (e.g. agony, despair and murder) or neutral (e.g. box, ear or kettle). After each word, participants were asked to choose whether the word was neutral or emotional (i.e. positive or negative), and how confident they were of their decision. The researchers found that the participants answered most accurately when responding to negative words – even when they believed they were merely guessing the answer.

Interestingly, our language often reflects the transfer from the physical attribute into the mental construct: “soft cushion” and “soft skills,” “heavy load” and “heavy duty,” “rough edges” and “rough treatment.” If we look at the examples above, we can find many expressions and metaphors that link similar physical experiences and perceptions. For instance, we can give a “cold shoulder” or a “warm welcome.” Our consciousness may be clean, but thoughts – dirty. When you attempted to avert a wrong and it continues anyway, you may state, “I wash my hands of the issue,” indicating that you are clean and not to blame.

According to research led by V. S. Ramachandran, director of the Center for Brain and Cognition at the University of California, San Diego, a region of the brain known as the angular gyrus is at least partly responsible for the human ability to understand metaphors. The angular gyrus is strategically located at the crossroads of areas specialized for processing touch, hearing and vision. The neurobiology of metaphorical thinking may be linked to synesthetic experiences where sensory or cognitive pathways join involuntarily and people may experience letters and numbers in colors, shapes and textures.

Perhaps, we can blame water metaphors for our cash flow problems. Nowadays, we speak of money not in “coin” terms but in “water” terms: liquid assets, slush fund, frozen assets, float a loan, currency, cash flow, capital drain, bailout, underwater mortgages.

Sources:

Britt, Robert Roy (2009, October 24). Cleanliness May Foster Morality. LiveScience. Retrieved September 1, 2010, from http://www.livescience.com/culture/091024-cleanliness-morality.html

Bryner, Jeanna (2008, October 23). Warm Hands Make People Generous. LiveScience. Retrieved September 1, 2010, from http://www.livescience.com/culture/081023-warm-hands.html

Dijkstra, K., Kaschak, M.P., & Zwaan, R.A. (2007). Body posture faciltates retrieval of autobiographical memories. Cognition, 102, 139-149.

Fine, C. (2006). A Mind of Its Own: How your brain distorts and deceives. New York: WW Norton.

Lupyan et al. (2010). Making the Invisible Visible: Verbal but Not Visual Cues Enhance Visual Detection. PLoS ONE 5 (7): e11452 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011452

Moskowitz, Clara (2008, September 16). Social Isolation Makes People Cold, Literally. LiveScience. Retrieved September 1, 2010, from http://www.livescience.com/health/080916-lonely-cold.html

Taylor W. Schmitz, Eve De Rosa, and Adam K. Anderson (2009). Opposing Influences of Affective State Valence on Visual Cortical Encoding. Journal of Neuroscience 29 (22): 7199 DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5387-08.2009

Valdesolo, Piercarlo (2010). The Neuroscience of Distance and Desire. Scientific American. Retrieved September 1, 2010, from http://www.scientificamerican.com/article.cfm?id=neuroscience-of-desire

Wellcome Trust (2009, September 30). Key To Subliminal Messaging Is To Keep It Negative, Study Shows. ScienceDaily. Retrieved September 1, 2010, from http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/09/090928095343.htm

Your brain on stereotypes and brand identities

“But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked. “Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” “How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice. “You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn’t have come here.”

“But I don’t want to go among mad people,” Alice remarked. “Oh, you can’t help that,” said the Cat: “we’re all mad here. I’m mad. You’re mad.” “How do you know I’m mad?” said Alice. “You must be,” said the Cat, “or you wouldn’t have come here.”

– Alice and the Cheshire Cat in “Alice In Wonderland” by Lewis Carroll

What comes to mind when you read the following list: “Emigrant Savings Bank, Dakota Roadhouse, St. Peter’s Roman Catholic Church, Starbucks, Equinox, Club Remix, Bank of New York, Shinjuku Sushi, New York City Law Department, Amish Market”?

How about this one: “Ground Zero Mosque”?

All the structures on the list above are within the one-block radius of the proposed construction of the Islamic center in Lower Manhattan, but the choice of words transformed a non-existent building into a symbol. In the words of NPR Senior Washington Editor Ron Elving, “the phrase sums up a controversy in terms so vivid and concise that neither journalists nor water cooler pundits can resist using the term.” He continues, “Of course, the phrase is also inaccurate and misleading. But how much does that constrain us when a phrase is so catchy and touches such a resonant emotional cord?” A recent memo to AP press discouraged the use of the phrase “Ground Zero Mosque”:

We should continue to avoid the phrase “ground zero mosque” or “mosque at ground zero” on all platforms. (We’ve very rarely used this wording, except in slugs, though we sometimes see other news sources using the term.) The site of the proposed Islamic center and mosque is not at ground zero, but two blocks away in a busy commercial area. We should continue to say it’s “near” ground zero, or two blocks away.

We can refer to the project as a mosque, or as a proposed Islamic center that includes a mosque.

Words shape our discourse, thinking and understanding in powerful ways. Labels captivate the brain, which is always busy searching for patterns and making predictions to make us comfortable in the world. The brain has developed organizational mechanisms that group data into categories based on similarities. Once information is stored in categories, the brain can use it to make predictions and inferences about new category members. Stereotyping is a by-product of how we process information. Stereotypes and labels are shortcuts for the brain used to conserve energy and resources. The problem with stereotypes is that they are like a crude chisel, shaping our perceptions while disregarding inaccuracies and illusory correlations.

While stereotypes can be triggered automatically, attention and reflection can inhibit and suppress stereotyping. For example, words can automatically activate stereotypes: people may spontaneously infer traits when they read a description of behavior. However, when people have an opportunity to evaluate stereotypes, automatic inferences are less likely to occur.

Interestingly, our brains recognize when we are biased although we may still behave against our better judgment. Psychologist Wim De Neys of Leuven University, Belgium came to this conclusion when he researched if stereotypical thinking happened because people failed to detect a conflict between a stereotypical response and a more reasoned response or because people failed to inhibit the tempting stereotypical response [PDF]. The participants in the study were solving a classic decision-making problem that was likely to trigger a stereotype while the experimenters watched their brain activation. Prior research established that the brain’s alarm center responsible for the detection of conflicts was the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) while the right lateral prefrontal cortex (RLPFC) played a key role in response inhibition. The study showed that the brain’s stereotype detection area became active regardless of whether the participant gave the stereotypical or rational answer. That means that our brains are good at recognizing stereotypes and set off signals that we need to proceed with caution. Inhibiting the stereotypical response is a different matter. The inhibition area became active only when the participant overrode the stereotype.

Is it easier to rely on stereotypes and jump to conclusions in online communication, which is often brief and devoid of the richness of information we can gain in face-to-face interactions? After all, we all have short attention spans and may not have time to stop and reflect. With anonymity, superfluous connections and minimal accountability, social networks aren’t the best examples of restraint and self-control either.

In the business realm, companies have long relied on the stereotyping and categorizing powers of the brain to create brand identities. After all, as a business, you want people to perceive and remember you in a certain way and believe that the next encounter with your products and services will be consistent with their expectations. Social media pose unique challenges and opportunities for brand identities. New brands are more likely to develop out of conversations with customers, fans, evangelists, rather than from one-way messaging and advertising. How can companies shape perceptions in the fluid online environment where they have less control over what’s being said about their brands?

It’s possible that social networks will cause brand identities to become more customer-centric and less static. Perhaps, it’s time to challenge stereotypes and strive daily to live up to our proclaimed values and uniqueness. Research supports the notion that consumers distance themselves from the marketplace labels and identity categories that turn into a cultural cliché, such as “yuppies,” “metrosexuals,” “hipsters,” while remaining loyal to their favorite products. Customers continuously recreate the meaning of the brands through various channels of interaction. To adjust to this new environment, we may need to replace automation with awareness and control with curiosity.

Awareness focuses our attention on our own thinking and behavior. It allows us to stop running the same train of thought and pretending that we know it all. It brings automated processes into our consciousness to notice and examine. It gifts us with the beginner’s mind.

Curiosity is a big motivator for the brain, which is wired to search for resources and information. Curiosity allows us to question assumptions and labels and open up to new perspectives. Curiosity encourages us to connect, engage and build relationships.

Where do you see challenges and opportunities for communicating your brand online?

Technology and the brain: On clicking, seeking, Massaro shoes, and dopamine

My computer slows down to a halt. I get impatient. I start looking for the cell phone. I can check Twitter, and Facebook, and email faster that way. I can’t find the phone. Instead, my eyes catch the cover of a coffee table book about luxury brands. It’s in Russian, and it has beautiful photos. I grab the book and start flipping through the pages in desperation because I feel like smashing the computer. And here it is, on page 252, this whimsical Massaro shoe…

During his 56-year career, Raymond Massaro has handcrafted shoes for Marlene Dietrich, the Duchess of Windsor, Claudia Schiffer, as well as fashion houses like Chanel, Christian Lacroix, John Galliano and many more. The Massaro brand began as a family business in 1885. Raymond Massaro’s grandfather, father and three brothers were all shoemakers. Massaro had hoped to be a professor of French or history. His father made him become a shoemaker, and later Raymond Massaro thanked him for that every morning. Because Massaro didn’t have kids, he worked out a deal with his long-term client Chanel for the sale of his business with the right to work there as long as he wanted.

As I study the brain-captivating image, the sense of computer-induced urgency dissolves. The brain is capable of about 8 seconds of focused attention when something distracts us from the current task. The Massaro shoe does the trick. It’s almost a meditative experience. I feel calmer now. I don’t mind staying in the high fashion world a bit longer.

Why do we feel that sense of urgency around the Internet and our social networks in the first place? Why are we constantly searching, checking, updating? The answer lies in the fact that our brains prefer stimulation over boredom. The brain is motivated by curiosity and the search for patterns. Washington State University neuroscientist Jaak Panksepp calls this the “seeking” system of the brain. It motivates animals to search for food, and it causes human brains to seek out information, ideas, connections.

When the brain is busy searching and predicting, it increases levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine, which is responsible for the sense of purposefulness and focused attention. Dopamine is even implicated in our internal sense of time. So, next time you waste hours clicking and seeking, blame your dopamine neurons. Interestingly, these neurons become even more excited when there is no pattern to be found.

The fluid world of the web, where information flows fast and novelty rules, fuels the brain’s urge to search. In Slate’s article “Seeking,” Emily Yoffe writes:

Actually all our electronic communication devices—e-mail, Facebook feeds, texts, Twitter—are feeding the same drive as our searches. Since we’re restless, easily bored creatures, our gadgets give us in abundance qualities the seeking/wanting system finds particularly exciting. Novelty is one. Panksepp says the dopamine system is activated by finding something unexpected or by the anticipation of something new. If the rewards come unpredictably—as e-mail, texts, updates do—we get even more carried away. No wonder we call it a “CrackBerry.”

We all run through information mazes. No wonder, it takes a Massaro shoe to pull my attention away from the computer. And unless your brand has the Massaro shoe equivalent, I’ll just keep clicking.