Emotionally}Vague by Orlagh O’Brien

Whenever I work with people on emotional regulation during conflicts, I like to ask where they feel the emotions in the body. Stress and emotional overload can show up as muscle tension, hair standing up, sudden headache, pit in the stomach, racing heartbeat, deep sighing or shallow breathing. The body reveals what the brain tries to conceal. We are wired to react fast to perceived threats. Often, by the time the mind catches up, adrenaline, cortisol and other stress hormones have already begun their work in the body, triggering the fight or flight response. If the threat is too overwhelming for the nervous system, the brain may numb the body through the release of opiates, sending us into a freeze. This may feel like we are not quite there, so we experience less pain and internal turmoil.

Whenever I work with people on emotional regulation during conflicts, I like to ask where they feel the emotions in the body. Stress and emotional overload can show up as muscle tension, hair standing up, sudden headache, pit in the stomach, racing heartbeat, deep sighing or shallow breathing. The body reveals what the brain tries to conceal. We are wired to react fast to perceived threats. Often, by the time the mind catches up, adrenaline, cortisol and other stress hormones have already begun their work in the body, triggering the fight or flight response. If the threat is too overwhelming for the nervous system, the brain may numb the body through the release of opiates, sending us into a freeze. This may feel like we are not quite there, so we experience less pain and internal turmoil.

The faster we can notice our physiological reactions, the more chances we have to dampen the amygdala activation, stop the emotional rollercoaster, and send the mental resources back to the prefrontal cortex where all the planning, decision making, and social control happen. It helps to practice emotional regulation in less threatening situations first to build up the resilience of the nervous system.

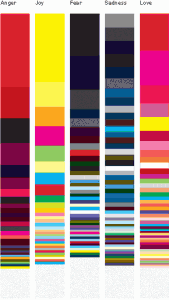

Therefore, I was thrilled to discover the Emotionally}Vague project about the body and emotion (Hat Tip to Kristin Butler @kirstinbutler on Twitter). This research project was launched by graphic designer Orlagh O’Brien and aimed to reveal patterns of visceral feelings in a visual, interactive manner. One of the steps in the survey asks the participants: “How do you feel these emotions in your body? Draw anything you wish.” The emotions are anger, joy, fear, sadness, and love. Orlagh O’Brien explains: “The answers were overlaid to create an averaging effect. It’s interesting to note how people draw around and outside the body and how the method reveals levels of intensity.”

You can see the results at http://www.emotionallyvague.com/results_02.php.

It is fascinating to see those patterns. Orlagh O’Brien’s method strikes me as a valuable tool in mediation and conflict coaching to help parties better express their emotions, understand each other’s reactions, ultimately learn to manage the self-defeating patterns, and perhaps, track changes over time.

Vulnerability doesn’t mean victimhood

What does being vulnerable mean to you? Most people don’t like feeling vulnerable, myself included. Without our protective stance, we feel exposed to the world that is ready to prey on our weaknesses. Yet, more and more research indicates that the expression of vulnerability contributes to our sense of well-being. In one of my all-favorite TED talks, Brené Brown, the leading researcher on vulnerability, explains why this may be the case.

What does being vulnerable mean to you? Most people don’t like feeling vulnerable, myself included. Without our protective stance, we feel exposed to the world that is ready to prey on our weaknesses. Yet, more and more research indicates that the expression of vulnerability contributes to our sense of well-being. In one of my all-favorite TED talks, Brené Brown, the leading researcher on vulnerability, explains why this may be the case.

Conflicts appear to be the worst situations for people to show vulnerability. After all, if you are in conflict, you already feel attacked. The typical fight or flight response is a survival mechanism wired into our brains. When our physical safety is at stake, the brain revs up our defenses, and it makes sense. While conflicts make people feel vulnerable, the typical reaction would be to cover up vulnerability with anger, attacks, defensiveness, and accusations. Are there any benefits to expressing vulnerability in situations that don’t involve risks of physical or emotional violence? Or will vulnerability simply lead to more victimization?

Vulnerability may show up as many things in conflict, such as:

- Sharing your feelings openly;

- Accepting the responsibility for your role in the conflict;

- Acknowledging mistakes, confusion, miscommunication, mistreatment;

- Giving the other side a second chance;

- Stepping into the unknown territory;

- Being willing to make a fool of yourself;

- Risking your reputation;

- Going against the majority opinion;

- Speaking your own truth;

- Risking being isolated from your own group;

- Delivering bad news;

- Letting go of the attachment to your conflict story.

What could conflicting parties gain by showing their vulnerability? Here are a few scenarios where the expression of vulnerability may lead to breakthroughs:

- When one side drops the attacking or defensive posturing and shows vulnerability, the other party may follow the suit. Then, the energy of the conflict shifts. When the parties drop their guard, it increases the connection and allows reciprocal expression of their humanity. They no longer need to pretend.

- Vulnerability is a sign of hope that the conflict can take a different path. Vulnerability breaks the patterns of the typical triggers and responses the parties go through.

- Showing vulnerability signals to the other side that you are comfortable with your own graces and follies. It conveys confidence in your ability to handle any feedback or reaction that may follow. When you show vulnerability, you reject shame.

- When you express vulnerability, you respect the other side enough to be honest and authentic, to let them know the real you.

- Vulnerability makes you less fearful and more creative. Instead of spending your mental and emotional energy to protect your image and beliefs, you feel the freedom to express yourself fully.

- When you show vulnerability, you take risks. Showing vulnerability can be both liberating and terrifying. And you can’t move forward without taking risks.

How else can vulnerability help in conflict management?

Resilience is empowering, but so is revenge

“Tomorrow is a new day; begin it well and serenely and with too high a spirit to be encumbered with your old nonsense.”

~ Ralph Waldo Emerson

There is power in the ability to take action and make a choice. Our brains like the sense of autonomy and control, after all, we want to feel comfortable in our environment. However, this human desire for autonomy and control can be expressed in a variety of ways, some of which may lead to more tension and longer conflicts.

There is power in the ability to take action and make a choice. Our brains like the sense of autonomy and control, after all, we want to feel comfortable in our environment. However, this human desire for autonomy and control can be expressed in a variety of ways, some of which may lead to more tension and longer conflicts.

In two recent discussion threads at The Conflict Coaching Guild on LinkedIn, we pondered the topics of resilience and revenge. Being resilient means being able to bounce back from life’s challenges, learn from different experiences, maintain a positive outlook despite setbacks and disappointments. Resilience requires a proactive, positive attitude and energy. It is hard to be resilient if your health is poor or you are depressed. Resilience is empowering. But so is revenge.

It can feel good to fight back when we are attacked even when we know that the revenge may cause more escalation. It turns out that our reactions to the punishment of bad social behavior range from reduced sympathy towards perpetrators to pleasure. The Prisoner’s Dilemma experiments show that even though the subjects are able to empathize and feel the pain of others, the activity in the pain-related areas of the brain slightly decreases when the participants feel the other side deserved a punishment. Moreover, when men (but not women) in the study watched a defector get punished, they showed additional activation in the pleasure circuit of the brain. Retaliating may feel so sweet because of the added sense of control we derive from our own actions.

The biological impulse to retaliate is strong. Conflicting parties are likely to be stuck in the continuous cycle of violence and revenge unless they find alternative ways to express their autonomy and choice of action. In essence, one side feels autonomous and fulfilled by punishing the other side, and vice versa. Remove the crutch of revenge, and the parties may feel lost and helpless. The challenge is to move beyond our biology and channel the need for autonomy into creative action and true resilience. Here are the choices:

| Revenge | Resilience |

| Blaming | Sharing responsibility |

| Defending | Acknowledging |

| Attacking | Forgiving |

| Stonewalling | Connecting |

| Threatening | Harmonizing |

| Resisting | Accepting |

| Listening selectively | Listening reflectively |

| Ignoring | Inquiring |

| Withholding | Sharing |

| Assuming | Clarifying |

| Catastrophizing | Reframing |

| Reacting | Anticipating |

| Judging | Witnessing |

| Victimizing | Empowering |

When we let go of revenge and embrace our own resilience, we regain the inner source of power. We no longer need an adversary to validate our significance. Instead, we begin relying on our own strengths to carry us forward.