From uncertainty to emergent meaning: How the brain tells stories

“Our perception of the world is a fantasy that coincides with reality.”

~ Dr. Chris Frith, neuropsychologist and author of “Making up the Mind: How the Brain Creates Our Mental World”

Conflict management by its nature involves a lot of uncertainty. The paradox is that uncertainty can be both a threat to the brain and a fuel for its creativity. The brain has an important job of keeping us comfortable and secure in the world by making sure that we understand what is going on around us. We want to know or be able to predict what happens next.

When uncertainty undermines our sense of control over our environment, it can cause stress. People would rather know the worst than fear the worst. The anticipation of negative emotional states influence our behavior and decisions. The dread of not knowing may be paralyzing.

Perhaps, it can explain, in part, why people get stuck in protracted conflicts. The conflict stories, identities, and behaviors, no matter how dysfunctional they may be, are familiar to the parties. The brain knows what to expect and what behaviors to choose. In contrast, the outcomes of the conflict resolution process are uncertain. They may require changes and adjustments in the usual behavior patterns. They brain is wired to avoid losses and conserve mental energy, which may mean the preference for the painful status quo. The change is more likely when the cost of being in conflict becomes too much to bear or when the current situation is so destabilized that there is no more certainty left.

At the same time, the brain is equipped to deal with ambiguity, search for patterns, and create meaning. So, what happens when the brain encounters information gaps?

Research conducted by neuroscientist Michael S. Gazzaniga sheds light on how the brain strives to create a complete picture. His experiments involved split-brain patients whose left hemisphere and right hemisphere were separated and didn’t communicate to each other due to a rare surgery procedure performed to treat severe epileptic seizures.

Researchers showed a spit-brain patient two pictures: a chicken claw was shown to his left hemisphere, and a snow scene was shown to his right hemisphere. The patient then was asked to choose from an array of pictures in front of him. He chose a picture of the shovel with the left hand, which was controlled by the right hemisphere of the brain, and the picture of the chicken with the right hand, which was controlled by the left hemisphere. When asked why he chose those items, the left-brain interpreter explained, “Oh, that’s simple. The chicken claw goes with the chicken, and you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed.”

Evidently, the right brain that saw the picture of the snow sent an impulse to the left hand to pick up the picture of the shovel. The left brain observed the fact that the left hand picked up the picture of the shovel and had to explain it. Because it didn’t know about the snow scene shown only to the right hemisphere, it came up with a story, which, in fact, wasn’t the correct interpretation.

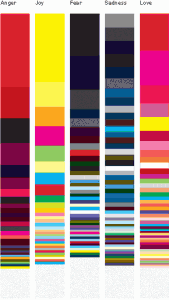

Similar experiments have been done with mood shifts. When a frightening picture was shown to the right hemisphere, the patient got upset. And while she denied seeing anything, she felt the emotional response and said that she was upset because the experimenter was upsetting her. Once again, the left hemisphere, which knew nothing of the sad picture but registered the emotional response, had to offer an explanation, and it turned out to be inaccurate. These experiments show that the left hemisphere of the brain will offer an explanation even if there are gaps in information although the interpretation may not be accurate.

On one hand, the propensity of the brain to spin stories may account for disagreement in how parties in conflict see the situation. On the other hand, it also offers the key to changing the stories that don’t serve the parties well. When we design a process that allows for new interactive patterns to emerge, we engage the natural power of the brain to create new interpretations and fresh solutions.

Here are some thoughts on how to make conflict management more brain-friendly:

- Encourage free exchange of information to minimize stress-generating uncertainty.

- Let the parties express their feelings and concerns regarding possible future scenarios to understand the impact of anticipatory emotions.

- Incorporate practices that support emotional regulation into the conflict management process.

- Promote the use of meta-cognitive skills, i.e. thinking about thinking.

- Relinquish the desire to fix and control. Adopt the mindset to experiment, learn, and improve.

- Give enough time and “white space” for the emerging understanding and insights to percolate to the surface.

- Allow for new modes of thinking and patterns to emerge through active listening, storytelling, inquiry, journaling, mind-mapping, role-play, improv, etc.

What else? Let your brain fill in the gaps.