How conflict management is like Parkour

“I can do Parkour for the rest of my life without even moving, just efficient thinking.”

~ Ryan Doyle

If you are not sure what Parkour is, here is how Wikipedia describes it:

Parkour (sometimes abbreviated PK) is a method of movement focused on moving around obstacles with speed and efficiency. Originally developed in France, the main purpose of the discipline is to teach participants how to move through their environment by vaulting, rolling, running, climbing and jumping. Traceurs (parkour practitioners) train to be able to identify and utilize alternate or the more efficient paths.

Better yet, watch this video “Ryan Doyle parkour in Mardin” to get a feel.

Since I can barely move around obstacles even in a slow fashion without knocking something over or bruising myself, Parkour is quite fascinating for me to watch. It also strikes me that conflict management is like a verbal Parkour. They have a few things in common.

While obstacles that parties in conflict face are not made of brick and concrete, they can sometimes give an impression that you are running into a wall. As conflict management practitioners, we help our clients navigate through their own obstacle course. We use a variety of tools and interventions, depending on the skills of the participants and the nature of the course. We may encourage storytelling to build trust. We give parties an opportunity and space to be heard. We question to uncover hidden negative assumptions and blocks. We reframe to deepen understanding. We trust the process to turn polarizing into problem-solving. But we can’t run the course for our clients.

Traceurs take the most direct path through an obstacle. They want speed, but they can’t compromise safely. Similarly, in a conflict situation, the desire to reach an agreement as quickly as possible has to be balanced against long-term relationship goals and the risk of false conformity. Just like one cannot expect to run a Parkour course successfully without proper training, we have to respect the time and pace it takes for the clients to prepare to deal with the issues effectively. Rush too much, and you risk the collapse of any agreement.

According to “Two Theories on Parkour Philosophy” from Parkour North America, “Parkour is a means of reclaiming what it means to be a human being. It teaches us to move using the natural methods that we should have learned from infancy. It teaches us to touch the world and interact with it, instead of being sheltered by it.” This need for self-expression, human connection and meaning is also at the core of conflict management. Just like traceurs feel the surfaces with their hands, our clients need to develop the trust in their ability to handle raw emotions without damaging their sense of self-worth. The hope is that through better self-awareness and more effective methods of social interaction, they may be able to drop the armor that shields them from the world and express themselves with openness, clarity and respect.

And there is more on Parkour philosophy and practice from Urban Discipline: “It is as much as a part of truly learning the physical art as well as being able to master the movements, it gives you the ability to overcome your fears and pains and reapply this to life; as you must be able to control your mind in order to master the art of parkour.” Ryan Doyle in the video above talks about mental rehearsal as a necessary step to program both the mind and the body for the course. Conflict management is also about mastering the mind. It’s about identifying old, unproductive patterns of dealing with issues and envisioning new possibilities. It’s about gradually focusing the mind on positive behaviors that create new pathways in the brain and strengthen them with enough repetition to turn them into a habit. It’s about turning uncertainty and negativity into curiosity and creative search for solutions.

The physical environment is essential to Parkour. While the influence of the physical environment on conflict management is less understood, research shows that it has a big impact on cognitive function and decision-making. The ‘broken windows’ hypothesis tells us that that public places with signs of decay and neglect encourage crime and antisocial behaviour. A recent study shows that messy surroundings also make people more likely to stereotype others. In contrast, interacting with nature dramatically improves cognitive function and restores our ability to exercise directed attention and working memory. It turns out that the mere presence of plants in an office setting boosts one’s ability to maintain attention. This interplay of our physical world, perception and behavior is of special interest to me. As Alva Noë put it, “Consciousness requires the joint operation of brain, body, and world.”

Last but not least, Parkour is also an art. It encourages people to appreciate the beauty of the movement and the surroundings. Art has a role to play in conflict management as well. From storytelling to visuals to improv, art can help people get in touch with their own emotions and cultivate self-awareness. Creative expression and creative play lower defenses and open up the mind to new possibilities, leading to insights and breakthroughs.

And sometimes Parkour encourages a different form of art, as in the video below (Hat Tip to @christophemorin on Twitter)

From uncertainty to emergent meaning: How the brain tells stories

“Our perception of the world is a fantasy that coincides with reality.”

~ Dr. Chris Frith, neuropsychologist and author of “Making up the Mind: How the Brain Creates Our Mental World”

Conflict management by its nature involves a lot of uncertainty. The paradox is that uncertainty can be both a threat to the brain and a fuel for its creativity. The brain has an important job of keeping us comfortable and secure in the world by making sure that we understand what is going on around us. We want to know or be able to predict what happens next.

When uncertainty undermines our sense of control over our environment, it can cause stress. People would rather know the worst than fear the worst. The anticipation of negative emotional states influence our behavior and decisions. The dread of not knowing may be paralyzing.

Perhaps, it can explain, in part, why people get stuck in protracted conflicts. The conflict stories, identities, and behaviors, no matter how dysfunctional they may be, are familiar to the parties. The brain knows what to expect and what behaviors to choose. In contrast, the outcomes of the conflict resolution process are uncertain. They may require changes and adjustments in the usual behavior patterns. They brain is wired to avoid losses and conserve mental energy, which may mean the preference for the painful status quo. The change is more likely when the cost of being in conflict becomes too much to bear or when the current situation is so destabilized that there is no more certainty left.

At the same time, the brain is equipped to deal with ambiguity, search for patterns, and create meaning. So, what happens when the brain encounters information gaps?

Research conducted by neuroscientist Michael S. Gazzaniga sheds light on how the brain strives to create a complete picture. His experiments involved split-brain patients whose left hemisphere and right hemisphere were separated and didn’t communicate to each other due to a rare surgery procedure performed to treat severe epileptic seizures.

Researchers showed a spit-brain patient two pictures: a chicken claw was shown to his left hemisphere, and a snow scene was shown to his right hemisphere. The patient then was asked to choose from an array of pictures in front of him. He chose a picture of the shovel with the left hand, which was controlled by the right hemisphere of the brain, and the picture of the chicken with the right hand, which was controlled by the left hemisphere. When asked why he chose those items, the left-brain interpreter explained, “Oh, that’s simple. The chicken claw goes with the chicken, and you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed.”

Evidently, the right brain that saw the picture of the snow sent an impulse to the left hand to pick up the picture of the shovel. The left brain observed the fact that the left hand picked up the picture of the shovel and had to explain it. Because it didn’t know about the snow scene shown only to the right hemisphere, it came up with a story, which, in fact, wasn’t the correct interpretation.

Similar experiments have been done with mood shifts. When a frightening picture was shown to the right hemisphere, the patient got upset. And while she denied seeing anything, she felt the emotional response and said that she was upset because the experimenter was upsetting her. Once again, the left hemisphere, which knew nothing of the sad picture but registered the emotional response, had to offer an explanation, and it turned out to be inaccurate. These experiments show that the left hemisphere of the brain will offer an explanation even if there are gaps in information although the interpretation may not be accurate.

On one hand, the propensity of the brain to spin stories may account for disagreement in how parties in conflict see the situation. On the other hand, it also offers the key to changing the stories that don’t serve the parties well. When we design a process that allows for new interactive patterns to emerge, we engage the natural power of the brain to create new interpretations and fresh solutions.

Here are some thoughts on how to make conflict management more brain-friendly:

- Encourage free exchange of information to minimize stress-generating uncertainty.

- Let the parties express their feelings and concerns regarding possible future scenarios to understand the impact of anticipatory emotions.

- Incorporate practices that support emotional regulation into the conflict management process.

- Promote the use of meta-cognitive skills, i.e. thinking about thinking.

- Relinquish the desire to fix and control. Adopt the mindset to experiment, learn, and improve.

- Give enough time and “white space” for the emerging understanding and insights to percolate to the surface.

- Allow for new modes of thinking and patterns to emerge through active listening, storytelling, inquiry, journaling, mind-mapping, role-play, improv, etc.

What else? Let your brain fill in the gaps.

Emotionally}Vague by Orlagh O’Brien

Whenever I work with people on emotional regulation during conflicts, I like to ask where they feel the emotions in the body. Stress and emotional overload can show up as muscle tension, hair standing up, sudden headache, pit in the stomach, racing heartbeat, deep sighing or shallow breathing. The body reveals what the brain tries to conceal. We are wired to react fast to perceived threats. Often, by the time the mind catches up, adrenaline, cortisol and other stress hormones have already begun their work in the body, triggering the fight or flight response. If the threat is too overwhelming for the nervous system, the brain may numb the body through the release of opiates, sending us into a freeze. This may feel like we are not quite there, so we experience less pain and internal turmoil.

Whenever I work with people on emotional regulation during conflicts, I like to ask where they feel the emotions in the body. Stress and emotional overload can show up as muscle tension, hair standing up, sudden headache, pit in the stomach, racing heartbeat, deep sighing or shallow breathing. The body reveals what the brain tries to conceal. We are wired to react fast to perceived threats. Often, by the time the mind catches up, adrenaline, cortisol and other stress hormones have already begun their work in the body, triggering the fight or flight response. If the threat is too overwhelming for the nervous system, the brain may numb the body through the release of opiates, sending us into a freeze. This may feel like we are not quite there, so we experience less pain and internal turmoil.

The faster we can notice our physiological reactions, the more chances we have to dampen the amygdala activation, stop the emotional rollercoaster, and send the mental resources back to the prefrontal cortex where all the planning, decision making, and social control happen. It helps to practice emotional regulation in less threatening situations first to build up the resilience of the nervous system.

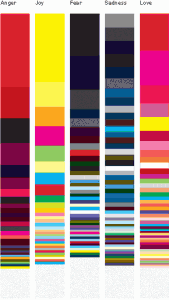

Therefore, I was thrilled to discover the Emotionally}Vague project about the body and emotion (Hat Tip to Kristin Butler @kirstinbutler on Twitter). This research project was launched by graphic designer Orlagh O’Brien and aimed to reveal patterns of visceral feelings in a visual, interactive manner. One of the steps in the survey asks the participants: “How do you feel these emotions in your body? Draw anything you wish.” The emotions are anger, joy, fear, sadness, and love. Orlagh O’Brien explains: “The answers were overlaid to create an averaging effect. It’s interesting to note how people draw around and outside the body and how the method reveals levels of intensity.”

You can see the results at http://www.emotionallyvague.com/results_02.php.

It is fascinating to see those patterns. Orlagh O’Brien’s method strikes me as a valuable tool in mediation and conflict coaching to help parties better express their emotions, understand each other’s reactions, ultimately learn to manage the self-defeating patterns, and perhaps, track changes over time.

Vulnerability doesn’t mean victimhood

What does being vulnerable mean to you? Most people don’t like feeling vulnerable, myself included. Without our protective stance, we feel exposed to the world that is ready to prey on our weaknesses. Yet, more and more research indicates that the expression of vulnerability contributes to our sense of well-being. In one of my all-favorite TED talks, Brené Brown, the leading researcher on vulnerability, explains why this may be the case.

What does being vulnerable mean to you? Most people don’t like feeling vulnerable, myself included. Without our protective stance, we feel exposed to the world that is ready to prey on our weaknesses. Yet, more and more research indicates that the expression of vulnerability contributes to our sense of well-being. In one of my all-favorite TED talks, Brené Brown, the leading researcher on vulnerability, explains why this may be the case.

Conflicts appear to be the worst situations for people to show vulnerability. After all, if you are in conflict, you already feel attacked. The typical fight or flight response is a survival mechanism wired into our brains. When our physical safety is at stake, the brain revs up our defenses, and it makes sense. While conflicts make people feel vulnerable, the typical reaction would be to cover up vulnerability with anger, attacks, defensiveness, and accusations. Are there any benefits to expressing vulnerability in situations that don’t involve risks of physical or emotional violence? Or will vulnerability simply lead to more victimization?

Vulnerability may show up as many things in conflict, such as:

- Sharing your feelings openly;

- Accepting the responsibility for your role in the conflict;

- Acknowledging mistakes, confusion, miscommunication, mistreatment;

- Giving the other side a second chance;

- Stepping into the unknown territory;

- Being willing to make a fool of yourself;

- Risking your reputation;

- Going against the majority opinion;

- Speaking your own truth;

- Risking being isolated from your own group;

- Delivering bad news;

- Letting go of the attachment to your conflict story.

What could conflicting parties gain by showing their vulnerability? Here are a few scenarios where the expression of vulnerability may lead to breakthroughs:

- When one side drops the attacking or defensive posturing and shows vulnerability, the other party may follow the suit. Then, the energy of the conflict shifts. When the parties drop their guard, it increases the connection and allows reciprocal expression of their humanity. They no longer need to pretend.

- Vulnerability is a sign of hope that the conflict can take a different path. Vulnerability breaks the patterns of the typical triggers and responses the parties go through.

- Showing vulnerability signals to the other side that you are comfortable with your own graces and follies. It conveys confidence in your ability to handle any feedback or reaction that may follow. When you show vulnerability, you reject shame.

- When you express vulnerability, you respect the other side enough to be honest and authentic, to let them know the real you.

- Vulnerability makes you less fearful and more creative. Instead of spending your mental and emotional energy to protect your image and beliefs, you feel the freedom to express yourself fully.

- When you show vulnerability, you take risks. Showing vulnerability can be both liberating and terrifying. And you can’t move forward without taking risks.

How else can vulnerability help in conflict management?